Picture "Oiseau bleu (Oiseau IV)" (1952) New

Picture "Oiseau bleu (Oiseau IV)" (1952) New

Quick info

limited, 8 copies | numbered | signed | etching on velour paper | framed | size 30.5 x 36.5 cm

Detailed description

Picture "Oiseau bleu (Oiseau IV)" (1952)

Towards the end of his artistic career, the flying bird became a central motif in the works of Georges Braque. Although birds also appeared in Braque's earlier still lifes, they evolved into an independent subject from the 1950s onwards. One explanation for Braque's fascination with this creature of the air, which lasted for several years, may lie in its representation of the artist's intense engagement with three-dimensional space and its translation onto the surface.

In an interview with the French art historian Jean Leymarie for the magazine "Quadrum" in 1958, Braque described his path to this motif: "In 1929, I first encountered the motif for an illustration of Hesiod. I had already painted birds in 1910, but they were embedded in still lifes, whereas in my current works, I am enthusiastic about space and movement."

The work offered here, "Oiseau bleu (Oiseau IV)" from 1952, depicts the figure of a bird in a flat, geometric perspective. The colour lithograph comes from the strictly limited and hand-signed small edition of only 8 copies.

Etching, 1952, edition of 8 copies on wove paper, numbered and signed. Catalogue raisonné Vallier 77. Motif size 19 x 29.5 cm. Sheet size 24 x 34 cm. Size in frame 30.5 x 36.5 cm as shown.

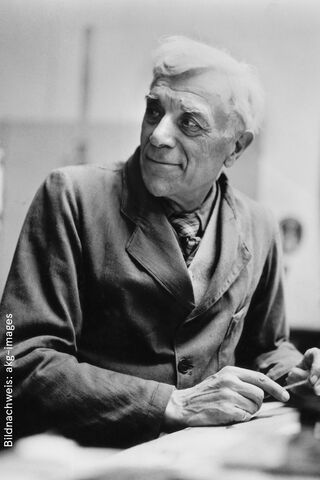

About Georges Braque

1882-1963

Georges Braque, the revolutionary of modern art and a classic figure of French art, left behind a magnificent oeuvre of prints: around 300 etchings, copperplate engravings, lithographs, and book illustrations. His life's work bears witness not only to an extraordinary joy in experimentation but also to a highly idiosyncratic pictorial imagination and creative power.

Braque stated the following essential observation: "We must be content with discovery and renounce explaining. There is only one valuable thing in art: the thing you cannot explain. A work that does not have a magical effect is not a work of art."

Before the First World War, Cubism emerged in 1908 in France, with its founding fathers being Georges Braque, who was born in Argenteuil, Val-d'Oise on May 13, 1882, and his friend and companion Pablo Picasso. Returning from the war, however, Braque pursued different artistic paths from Picasso, which in turn linked him to Henri Laurens and Juan Gris.

The guitar, vases and tables were central motifs in the Cubist paintings. The pure colours that still dominated his early fauvist landscape paintings subside to a grey-brown colour palette. As an antithesis to Cubism, Braque developed the collages, creating a new pictorial reality with scraps of wallpaper and newspaper clippings. This was followed by landscapes again in the 1930s, which, however, bear witness to a still-life-like structure. From 1938 onwards, the traditional theme of the studio became important to the artist, enriched by the motif of birds with a mystical component.

In the last years of his life, the artist presented himself not only as a painter and sculptor but also as a jewellery designer. His "Bijou Braque" combined the art of jewellery with the aspiration of the artist. He incorporated Greek motifs into over 100 designs. A dozen of them were even purchased by France. His art was so highly regarded that, in 1961, he became the first artist to have an exhibition dedicated to him in the Louvre during his lifetime. When Braque died on August 31, 1963, in Paris, the French Minister of Culture, André Malraux, made his status clear once again: "He is at home in the Louvre with the same right as the Angel of Reims in his cathedral."

The overlaps and saturations in Braque's works do not appear intensely spatial but are an integral part of the picture plane. This is why his paintings appear aesthetic and sensitive. His works "activate" the sense of seeing, and the pictorial impression is always ambiguous. The motifs are dissolved into colourful and formal structures. The form has autonomy and, at the same time, is integrated into larger constellations. All major museums exhibit his work in prominent positions.

The field of graphic arts, that includes artistic representations, which are reproduced by various printing techniques.

Printmaking techniques include woodcuts, copperplate engraving, etching, lithography, serigraphy.